This page of the website is devoted to tales of travel! Let us know where you went, how you went, with whom you went, and what happened (in no particular order). If you recommend a particular travel company, please share. Cities? Accommodations? We look forward to your posts!

KAY JESTER BYERLY’S TRIP ALONG THE SILK ROAD

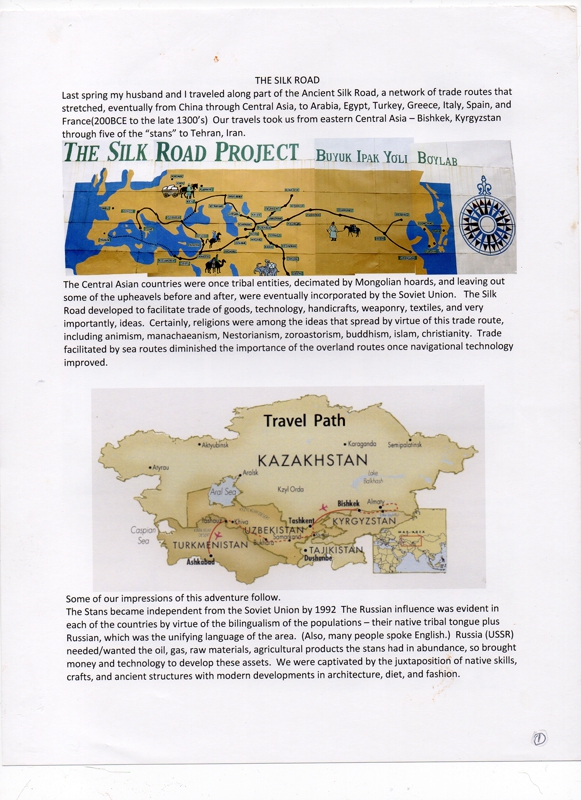

THE SILK ROAD

This is a fascinating look into a world that, for most of us, is relatively unknown. I am posting single pages of her 36 page travelogue. You can zoom in on the page to enlarge it enough to see it clearly, or, on a Mac, press (Command) and (+) at the same time. THANK YOU KAY, for this labor of love!

JUDY SAYLER OLMER’S TRIP TO ROME (Fall 2016)

Judy joined a Smithsonian Journey trip to Rome and reports on it HERE. Sounds like a whirlwind of a wonderful series of experiences!

TRAVEL AND THE AGING BOD

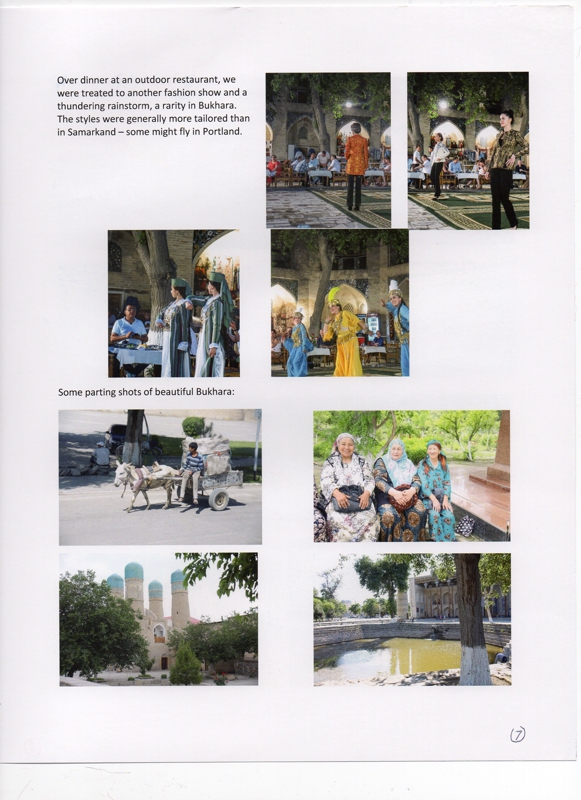

Judy Sayler Olmer wrote recently of her challenge with adjusting to time change (jet lag) when traveling. It brings to mind other possible reminders that we are not as young as we used to be, or that we might think we are deep inside. Read her essay HERE and join in to the discussion!

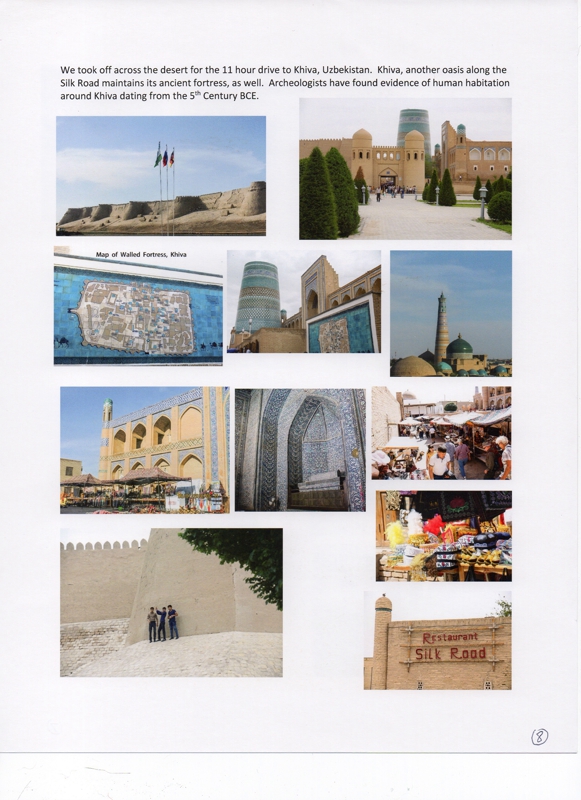

GREECE (Posted 07-24-16)

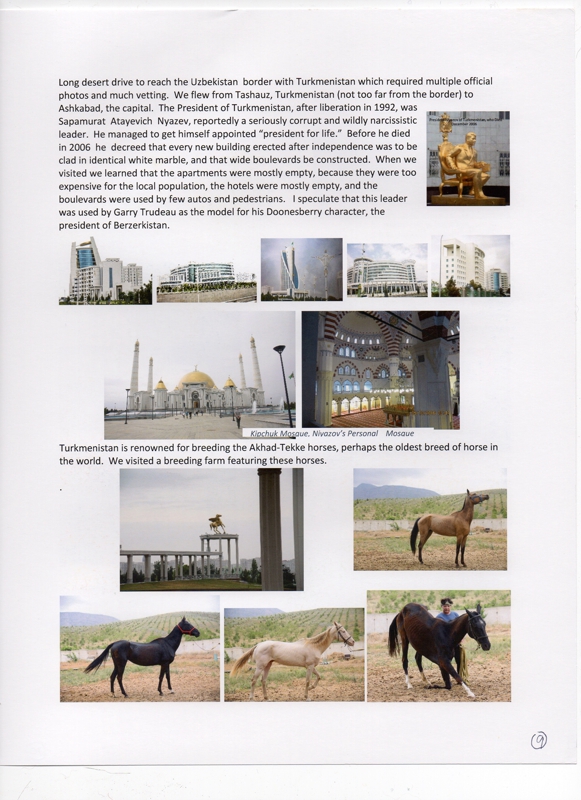

Kate Bracher has accompanied her partner Cynthia Shermerdine (Bryn Mawr ’70) on an ongoing archaeological dig for many years. The work is fascinating, and the dig was featured on a recent MBPN series on Greece (with a cameo appearance by Cynthia!). Read about it HERE. Contact Kate for information about travel to Greece.

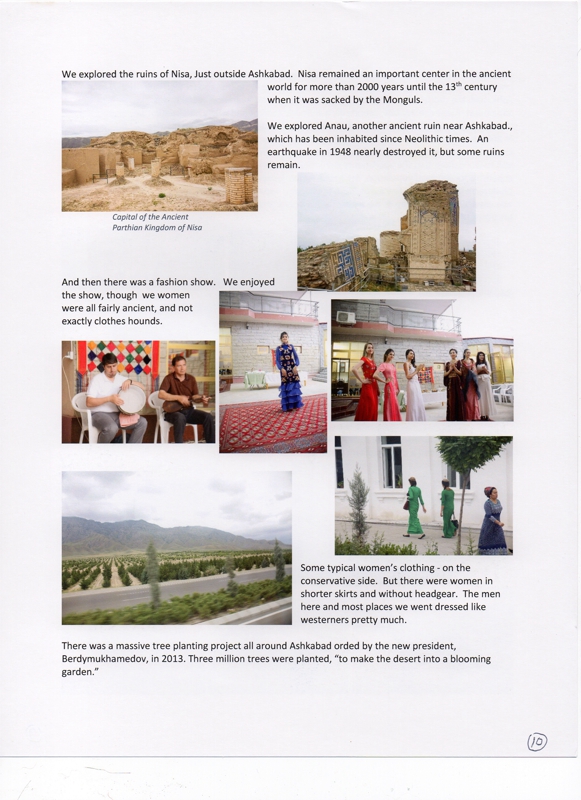

ICELAND (Posted 07-17-16)

Sandy Germond Pritz and her husband Howard, inveterate travelers that they are, recently traveled to Iceland. For a wonderful overview of their trip, you can read Sandy’s write-up HERE. Please note her comment that she would love to talk to anyone who might be planning a trip there. Photographs are below.

U.S. TRAVEL ON THE MIGHTY MISSISSIPPI

Sandy Germond Pritz and her husband Howard joined Bev Burke Eighmy and her husband Tom on a trip on the paddle-wheeler the American Queen between Memphis and New Orleans. Sandy writes about it HERE. Looks like they had a glorious time! (Click photos below to enlarge).

7 Days in Cuba

With Some Special Mount Holyoke Spice

Judy Sayler Olmer

February 2013

Probably like a lot of Americans, I have been mildly interested in seeing Cuba for myself for the past several years. It hadn’t made it anywhere near the top of my bucket list when an unanticipated opportunity made me decide this was the time. Last July, Nancy Rich Coolidge wrote to ask if I would be interested in seeing Cuba. She had gone there in April 2012 with a Sausalito CA company, Cross-Cultural Journeys. It was such a great experience that she decided she’d like to organize a group to make a similar trip from Jan. 18-25, 2013. I thought about it for a couple of nanoseconds and wrote back to say “yes!” Thus, the group was made up of “friends of Nancy,” with a few additional “friends of friends of Nancy.” Five of us were Mount Holyoke classmates, including Kate Frum Buttenwieser, Dodie Jeck Gutenkunst, and Becky Broughton Wood. Nancy’s sister Cynthia Rich Bonnes (MHC ’62) also came with her husband. Since Nancy is a pretty special person, the group of twenty three was as congenial and interesting as any I’ve ever traveled with. Nancy was trip manager. With Wilford Welch of the Cross-Cultural Journeys Foundation, whose wide-ranging contacts in Cuba provided several “extra” opportunities, and an absolutely fabulous Cuban guide, Yovani, to explain it all to us, we had a great team.

About CCJ:

CCJ operates tours to Cuba under license from the US Treasury Department and must meet rigorous standards to show that it is not taking “tourists” to Cuba, but fulfilling a “people to people” mission, emphasizing cultural experiences and contact with the Cuban people, not the government. Standards for travel to Cuba have been eased under the Obama administration, but Treasury is under constant pressure from anti-Cuba hardliners to decertify companies they believe step over the line. Thus, many licenses were held up last year, application forms were made more onerous, and some companies were de-certified. We were advised about fairly tough restrictions on how much we could bring with us and what Americans or Cuban authorities might fuss over. However, the process of exit and entry in both directions was extremely smooth—reentry to Miami was much improved from an unpleasant experience I had there about 10 years ago coming home from Ecuador. I didn’t try to bring back anything forbidden, like Cuban cigars or rum, so I can’t guess whether the airport dogs would have sniffed that contraband. Arts and craftsare allowed, though you must accomplish everything you do in Cuba in cash—trading paper dollars for the Cuban tourist currency known as CUC’s. No credit or debit cards, no traveler’s checks, nothing that would involve a US bank in any way.

The itinerary:

We spent only a week in Cuba—five nights in Havana, with a two-night excursion to Cienfuegos and Trinidad on the south coast. I notice that Road Scholar has a two-week itinerary covering much more of the country, and I’d be interested in talking to someone about how that worked. For me, the breakneck pace we kept up during our 7 days meant that I’d have had to have a day “off” from touring and people-to-peopling to continue.

What is there to do in Havana? You could spend days investigating Habana Vieja—the Old City—which is a UNESCO-designated World Heritage site representative of the best of Spanish colonial architecture. (Havana is often described as the key or entryway to the Spanish colonies in the Caribbean.) Restoration has been underway for many years, but was made a priority after the implosion of the USSR, when Cuba began to emphasize tourism and money began to come in from the West. Many of the colonial buildings have been restored to a fine level. But it is a process, there is never enough money, and everywhere, you see the contrast between stunning buildings painted and trimmed in pastels and crumbling ones which may collapse before their turn arrives. Cubans are living in many of the old buildings, so laundry hangs from many balconies. We enjoyed a lecture from a Cuban architect (and comedian) on the restoration process. He showed slides of some of the individualistic and hilarious steps residents have taken to shore up and/or decorate their buildings, results that horrify him because they destroy the unity of the Spanish colonial architecture that is being preserved—he would like the government to take a stronger hand in regulating this homeowner activity, but it’s hard not to sympathize with the residents.

Everyone here seems to have heard about the ancient US automobiles that Cubans have kept moving since the 1940’s and 50’s. They are in evidence all over Havana, though increasing numbers of more recent European and Asian-made cars are operating as well. The flashy old Chevrolets and Cadillacs are kept in amazing condition esthetically; they are a bit rough in operation. During the Soviet years, mechanics modified Soviet-made parts to function in the old cars. With their withdrawal, usable parts have been a real problem, but Yovani told us that Cubans have developed small businesses fabricating parts that will work. So if one needs a carburetor or a muffler, one can find a friend’s brother in law who makes the part. Because of the old cars and a wide variety of other forms of transport, such as pedicabs, small 3 wheeled vehicles called “Coconut taxis,” and horse-drawn carriages, Havana streets are indeed a photographer’s paradise. For our final dinner at the home of local artist in a leafy suburb of Havana, the CCJ representative hired a fleet of six stunning convertibles from the 50’s (an entirely appropriate vintage for our group!) and we drove miles through the city streets with the drivers honking, and us cheering and waving to each other as we caught up at traffic lights. It’s fair to say that we attracted attention even on Havana’s lively streets. Havana is no museum, though.

The old city is built around a number of public squares, and Cuban life takes place everywhere on the streets and in those squares. Because so many people live in crowded and uncomfortable circumstances, and because the climate is mostly good, they spend a lot of time outdoors. Groups of school children run and play n their uniforms in the squares; Hawkers are selling corn on the cob and flutes of roasted, salted peanuts. Stilt-walkers and street performers of all kinds are everywhere. And of course, shopping for basics is an all-day undertaking in Cuba, and people must often walk long distances. So the streets are alive with people. They are also alive with music. I had been told, but still was surprised by how pervasive music is in Havana. Small bands play Cuban, Latin, and even American music in restaurants and on the streets. In the restaurants, they move from area to area, and at every break, the band collects tips and sells CDs. The quality is generally good, though at times we felt a bit hemmed in by bands playing too loud or too close for comfort. The first time we were in the wonderful Plaza des Armas, ringed by sellers of old books and magazines, a large and excellent orchestral band was playing a concert. They played a variety of songs, none of it “oompah” music, including orchestral music for bands. It was really wonderful, and I hated to leave.

On our forays in Havana, we visited:

–The Museo de Bellas Artes, an impressive collection of mostly Cuban paintings and other works, showing the progression of art history in Cuba through similar stages and styles to those seen in Europe or North America.

–Orgopanico Alamar, an organic farm in a reclaimed industrial area where an independent company is growing produce and herbs and developing organic methods and products, including some with medical benefits. The farm has a giant worm farm under a plastic roof to produce the mulch that feeds and protects their beautiful vegetables. Cuba was forced into organic farming after the collapse of the USSR, when it was unable to import the fertilizers and pesticides collectivized agriculture had relied upon. Given the wonderful climate, it is sad that Cuba continues to import most of its food.

–Ernest Hemingway’s Cuban home, Finca Vigia. This was one of the best historic homes I’ve seen, even though visitors cannot go inside. I believe that it was restored with major assistance from the US National Trust. We had to view the house through the large doors and windows, but something about its spaciousness and open quality meant that you had good views of everything. There are thousands of books in cases around the rooms. After Hemingway’s death in Idaho, his widow took what she wanted, but left most of what was there—so it gives a good impression of what daily life might have been like chez Hemingway. Visitors can also climb three stories to a tower workroom the author’s wife had built for him. His small portable typewriter is there, with a telescope and an expansive view to all four sides. The Pilar, the writer’s yacht, is maintained in pristine condition nearby. Hemingway left the yacht to Gregorio Fuentes, the local friend who was his model for “The Old Man and the Sea,” and when Fuentes died a few years ago, he left the boat to the museum. We also stopped at a bar in Cojimar where Hemingway spent a lot of time. There are pictures everywhere in the bar of Hemingway, the Pilar, and the old man. In Old Havana, we had lunch one day at the Bodeguita del Medio, a favorite haunt of Hemingway before he bought the Finca.–a community art project in a suburb where students have painted murals on walls along several streets and constructed tiled seating and a garden at a corner. The leadership and materials all are donated; there is no government support. The volunteers took over a huge, degraded old water tank and refurbished it to serve as classroom, workroom, and gallery, and they have obviously done great work with local youth. The project put on a program of music and dancing, eventually pulling almost everyone into the circle. Cubans seem ready to break out dancing at any moment, as if they are in a Fred Astaire movie.

–Estudio Taller Fuster, the studio and home of one of Cuba’s most famous artists, as well as his artist son. Fuster is compared to Picasso in the way he works with ceramics and ceramic tile; he and his son paint as well. The studio—and indeed much of the neighborhood—is covered in fanciful tile structures that bring to mind a fantastic amusement park with pools and arches and animals and murals, all constructed of tiny, brightly colored tiles.

–ISA, the national art school, which was created relatively soon after the revolution, using the golf course of Havana’s toniest country club—a club that had denied Batista membership as a mulatto. A novel complex of buildings was designed by Cuban architect Roberto Porro to include schools of music, dance, artes plasticas, and theater. The complex was not completed as planned, but what exists is very interesting—architectural forms described as representative of the female body (I saw buildings reminiscent of Moorish construction in Spain), with large, well-lit spaces for students of painting, printmaking, etc, sprinkled with intriguing open spaces and atria for relaxing. As a complete non-expert, the school seemed to me to have good equipment for printmaking, and large studio and gallery spaces for students of painting. Entry is highly competitive, student numbers are not large, and for Cubans, the education is free. We saw a lot of very good work, and one member of the group purchased a print from a run from which a similar print had been recently sold to the Tate Gallery in London. The artist met him at the hotel that evening with the print and the export papers needed to get it out of the country and into the US, and he paid in cash.

–the Yoruba Museum, a museum of the African religion called Santeria, that was melded with Roman Catholic practice by the slaves who brought Santeria with them to Cuba. From the museum, we caught a ferry across the harbor to a suburb called Regla, where we visited a Santeria-influenced church. A service was about to begin, and most of what was visible in the church and the multi-racial congregation was indistinguishable from what one would expect in a small Catholic church in the Third World. There was a “black Madonna,” and we knew from the museum that that has significance in Santeria. Outside, women were selling Santeria dolls, beads, and other regalia.

–quite a few of us had dinner at the legendary Hotel Nacional and stayed to see the Buena Vista Social Club. Two of the members of the original group played or sang that night—one of them a very old woman who sang and danced so provocatively that, again, she energized an entire room to get up and boogie. The music was a lot of fun…to a point. It went on a little too long and too late for me. The hotel has a small museum with photos and mementos from the glory days in the 30’s, 40’s, and 50’s when movie stars and Mafiosa were regular customers. Our guide told us that the hotel itself, while still open for guests, is not very good and badly needs refurbishing.

–finally, just five of us, accompanied by Yovani, saw a baisbol game between the Industrialists (one of Havana’s two teams) and Mayabeque (a Cuban province). It was a very good and interesting game–definitely a cultural experience. The Industrials (istas?) won 6-3, and were dominant throughout. Their pitching and batting were stronger, though fielding was sharp on both sides. There were no ads, no bullpens, no on-deck circle, minimal scoreboard. However, the field looked well tended. There was no food or drink, definitely no beer. We guessed the stadium seated 15,000 or a little more, but only 1,500 or so were there that night. We had excellent seats about 13 rows back, just behind and slightly to the right of home plate. Pretty basic, but we had paid less than $3 for them. The hoi polloi pay 5 cents for cement bleachers. A few innings in, I looked around our section and realized there were only Americans, except for Yovani. We totaled perhaps 20, probably all tourists. So, in the 7th inning, we stood up and sang “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” which felt a lot like the national anthem.

Our trip to Cienfuegos and Trinidad

This was a trip of about four hours to the southern coast. We stopped at a small museum of the Bay of Pigs. I haven’t been to Vietnam, but this must be a smaller version of the Hanoi museum celebrating how they conquered the traitors and their Norte Americano enablers. Pretty hard to argue with the abject failure of the Bay of Pigs operation. We went from there to lunch at the (irony!) Cienfuegos Club, a yacht club from the old days—a lovely Victorian building surrounded by palm trees. There were in fact a few yachts tied up at the pier in back! From there, we drove into Cienfuegos proper. I had known that city primarily as a port where the Soviet navy visited and the Soviets delivered military and other equipment. But Cienfuegos turned out to have a perfectly beautiful, leafy central square with magnificent and well restored public buildings surrounding it—a Cathedral, a theater, the governor’s palace, etc. We spent a bit of time looking at these buildings, then were taken into one of them for what was described as a “coral” concert. I think most of us expected something like a high school chorus. What we heard when the very lovely and graceful young conductor lifted her arms was an exquisite a capella choral group of 10 men and 10 women, most rather young, but a few of them older. The Cantores de Cienfuegos sang a wide ranging assortment of music—from early Spanish church music to Cuban and Latin rhythms to “Shenandoah.” At the end, I hoped they would have a CD to purchase. They have been invited to perform in Seattle, and efforts are underway in the US and Cuba to raise the money and obtain the required approvals for their trip.

We stayed for two nights in a hilltop hotel in Trinidad, a small colonial city. On our one real day there, we traveled to the Valley of the Sugar Mills, where we visited the only colonial home remaining from the days when wealthy planters settled here to harvest the crop that underpinned Cuba’s economy, using slave labor. At the rear of the gracious colonial home was a sugar mill under cover. A guide illustrated how the cane was crushed to release the juice. This part of the work was done by oxen, but overall, it would have been a harsh life. We visited a maternity clinic for women with problem pregnancies or young teenage girls without family support—a place where women can go to spend weeks or months in a facility where they are cared for. The actual births take place in a hospital; this place provides prenatal care and counseling. In Trinidad, too, there were beautiful buildings from the colonial period, but the whole town needs a lot of work. Several people returned to the city in the evening for salsa lessons and dancing. Then, back to Havana for two more nights.

Food:

Speaking just for me, food is not a reason to visit Cuba. We ate in both the government-run restaurants and the privately-owned paladars, some in private homes, some now larger. We were eating much better than the average Cuban, both in quantity and quality—we’d have had a lot more meat or fish, for example. But the food was remarkably similar in most every place we ate. Rice and beans are universal, as are plantain chips. We generally had a choice of chicken, beef or fish. Or chicken, pork or fish. Sauces were fairly bland. There were one or two places where the sauces were notably good, or the fish was especially well cooked. But by and large the meals were pretty interchangeable. Sadly, we were advised not to eat raw vegetables or fruit, so we had to leave a number of beautiful salads untouched. One evening, the group was divided, and 8 of us went to each of three very well known paladars. My group—MHC ’60, plus a few) ate at the Vistamar in Miramar. It specialized in seafood, and that was very good. Another group went to Le Chansonnier, where the cuisine was Cuban/French and may have been quite different. A third group went to La Guarida, the restaurant that figured in “Strawberries and Chocolate,” and they also enjoyed their dinner, as well as an impressive and strange location in a ramshackle old building that seemed so near falling down that it could not possibly house the restaurant. One memorable day, we lunched at a Chinese restaurant, Tien Tan, in Chinatown. The food was excellent, memorable, very Chinese. I fell on it, and it was my favorite meal. Hotel breakfasts were large and varied, with plenty of choices to fuel the day.

Drink:

I had more Mojitos that week than I have had in my previous life. A complimentary mojito was standard at most lunches and dinners, and amazingly, the very best one turned out to be a virgin mojito, kind of a mojito slurpy. Rum drinks were generally available and cheap. I had assumed I would not be drinking any wine, since it tendsto be unavailable, pricey, and poor in less developed countries. Imagine my surprise to find Chilean and Argentinian wine at $3 or $4 a glass. No one seems to have yet advised the Cubans that they could charge a lot more for wine than they do. Cuban beer is quite good, and we quickly separated ourselves into aficionados of Cristal (light) or Bucanero (medium bodied) cerveza. Coca cola is also available—from Mexico.

Lodging:

This was one of the big surprises. In Havana, we stayed on the edge of the old city at the Hotel Saratoga, which goes back about 100 years but had recently been totally restored.It was superb, with nice rooms, and excellent food and service. We had free wi-fi in every room. I did assume the government monitors the guest computers. There was a rooftop garden with a swimming pool and a gorgeous view of the city, an excellent place to have a nightcap of seven year old rum—or whatever. In Trinidad, we stayed in a hotel more like what I had expected—a rather careworn place with 1940’s style motel rooms drifting up a hillside with, however, a lovely view of sunrise and sunset over the colonial town. Food was not very good, but we enjoyed dining on a terrace near the pool. We were told that one of Cuba’s problems with the tourism boom it is experiencing is that the infrastructure is not yet there for handling large numbers of visitors from the US, though they have had a lot of visitation from Europe, Canada, and Latin America for several years. A lot of the hard currency coming in is going to enlarge and improve those facilities, but the effort has a way to go yet. Because of the US embargo, I was surprised that we had CNN in both hotels—CNN international in Havana, and regular CNN—from home—in Trinidad. I saw parts of the Presidential Inauguration at the latter. We also saw ESPN and US sports on TVs at many bars and restaurants. Cubans are big fans.

–People to peopling and “humanitarian gifts.”

Several of the encounters I’ve mentioned were intended as opportunities to meet ordinary Cubans, not just those involved in the tourist industry. These included the community art project, the maternity clinic in Trinidad, and a visit in the Hemingway town of Cojimar to a Baptist minister, Pastor Jimmy, wife Gripssy, and son Jonathan, who house a Baptist church in their home, and perhaps the organic garden and the Santeria outing fell into that category. We were able to ask fairly searching questions, and really enjoyed our contacts. We asked Pastor Jimmy about whether the government presented any problem with his social outreach ministry. He answered that they received no support from the government, but, “thank god, they have not interfered with us, either.” In preparing to visit Cuba, we were asked (and I was separately advised by people who spend time in Cuba) to bring along “humanitarian gifts.” These were things like over-the-counter medications and personal care products, along with arts and crafts supplies for children. All of these things are hard and expensive for most Cubans to obtain. Though medical care is free, and reasonably good, it is very difficult to find simple things like aspirin, band aids, soap, shampoo and deodorant. We had quite a stash of such supplies when we put them all together, and Nancy made up bags of such gifts to present to the maternity clinic, Pastor Jimmy and his wife, and to the community art project, large bags of art supplies for the students. Clearly, the gifts were welcome, and make a difference to people with limited access to the convertible currency that makes life in Cuba easier.

So, what do you think?

This was an intellectually complicated and challenging trip, and—as often happens—I’ve come home determined to do a lot more reading. Cuba is changing, it’s clear, though a National Geographic article last November showed that young people continue to try to leave the island because they lack opportunities. The Cuban government recently announced that it would free up exit visas for most citizens, and we’ll see how that goes. It will be expensive to secure passport, visa, and airfare, and perhaps to obtain entry to countries to which Cubans want to travel. But if it actually works, it will help. We felt that the people we spoke to spoke pretty frankly. No one seemed very cautious about criticizing the government’s policies or other aspects of life in Cuba—or for that matter, making jokes about the Castros. At the same time, we saw what appeared to be genuine pride in the accomplishments of the revolution, in particular universal literacy and medical care, as well as the reported fact that Havana and Cuba are extremely safe. (I can’t vouch for this, but we were told regularly that we need not worry about walking around on our own; we just weren’t given much time to do so!) The children and teenagers we saw all looked healthy, well fed, well-dressed and well-cared for. Yovani and others we spoke to frequently contrasted the situation today with the very harsh time in the early 90’s known as the “Special Period” following the collapse of the USSR, when Cubans suffered real want and controls were tight. People generally seem to assume that Fidel Castro is no longer a significant player, and are hopeful that his brother Raul (also in his 80’s) is more flexible and that life may continue to get better.

The space for operating small private businesses is growing. Of course, the leadership could change course at any moment, and who knows who might take over after the Castro brothers die?

Cuban Local Economy:

One of the most bizarre features of the current Cuban system is the dual currency, in which tourists change hard currency for Cuban Convertible Pesos (known as “CUCs” or “cooks”), on a more or less 1/1 basis, after the government takes its 13%. Locals are paid and buy supplies in the plain old Cuban peso, which is not convertible and is worth almost nothing even in Cuba. We were given figures for Cuban salaries which sounded all but impossible–$35 a month? Those figures are calculated, I think, by using the street value of Cuban pesos against the CUC. There is no official exchange value. Many necessities are very cheap or free—bus transport, rent, staple foods, health care. Many staple foods and supplies are rationed, and every Cuban has a ration card allowing him to buy the approved amount of rice, beans, etc. So one can live even on these small salaries, and families can put together several salaries to do OK. The problem comes when anyone who has no access to CUCs wants to buy pretty much any manufactured product, anything that is imported, and the kind of luxury goods that are sold in Cuba, including, say, the evening at the Buena Vista Social Cub. Those associated with the tourism industry receive tips in CUCs that almost certainly total much more than their salaries. Many Cubans have relatives or friends abroad who send or bring money and hard currency products that can be used or sold. Others—artists, for instance–receive CUCs for their work. Well paid Cuban professionals—doctors, engineers, baseball players—may receive much better salaries than ordinary workers, but those salaries won’t buy anything denominated in CUCs, either. This has resulted in a system with truly bizarre incentives, in which well trained and educated professionals may work instead as waiters or musicians, because they can earn so much more serving tourists. One positive change that could take place in Cuba in the near term would be the end of this crazy currency situation, which understandably causes a lot of resentment—not only of the visitors, but of fellow Cubans who have access when you have none.

All of this leaves visitors to Cuba in a bit of a moral quandary. There is so much to enjoy, but there is a dissonance to eating food that would hardly be available to Cubans; bringing in tubes of toothpaste, bottles of shampoo and soap to give away, while your hotel provides luxury products for your use; realizing that the musicians entertaining you are doing it because of the hard currency tips and might be doctors. I’m not suggesting that we should not visit Cuba—on the contrary, I’ve long been convinced that the US embargo and prohibitions on travel are counterproductive, ineffective, and positively un-American. Nothing I saw on this trip changed that view. Moreover, Cuba isn’t the only poor country Americans visit where we enjoy advantages locals don’t have. One hopes that by providing jobs and tips to the population—in this case, bringing in humanitarian gifts–we are doing some good.I think that most Americans see the Cubans who left Cuba for the US as a notably talented and productive group of immigrants, a real benefit to the US. Those who came early mostly came with education and, in some cases, considerable resources, but not all did, and like all immigrants, they have had to find jobs that may not have used their training or been what they were used to, and they have succeeded. What I perceived in Cuba is that the population that has been left behind is also talented and productive, very well educated by world standards and with a real entrepreneurial bent that has not been bred out of them in 50 years of Castro’s rule.

I was also struck by a difference between Cuba and other socialist states I have visited. In the former Soviet Union, in the Eastern European satellites, there was a grayness, both visual and atmospheric. People generally seemed downtrodden, unhappy, suspicious, a little hostile. Frumpy. This is not what Cuba looks or feels like—there is color, movement, laughter, imagination. There is that music. Probably it is the Caribbean culture that survives whatever political and social challenges people live with. Good luck to them!