Sue Bradley Cabot and Dana Feldshuh Whyte were co-presidents of our class from 2000-2010, and were responsible for getting the first class website off the ground. One of their many lasting contributions was the creation of ‘Birthday Biographies’ of women who made a difference in the life of the author of the biography, all with a connection to Mount Holyoke. It is fitting and proper that these be carried over to the new class website.

January

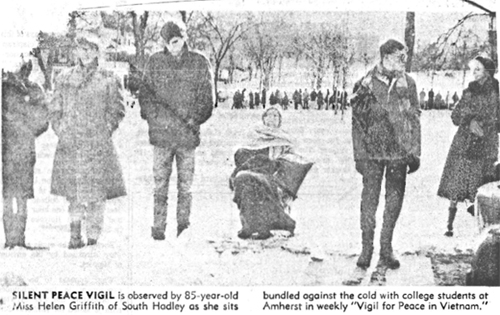

Helen Griffith

January 24, 1882 – October 16, 1976

Helen Griffith was the model of a dedicated teacher. After earning a B.A. at Bryn Mawr (1905), a master’s degree at Columbia, and a Ph.D. at the University of Michigan, she served on the Mount Holyoke faculty, in English, from 1912 until retirement in 1947, and when she retired she taught some more, first at Bennett College in North Carolina, later at Tougaloo University in Mississippi, and finally at Piney Woods School, also in Mississippi.

She went to Tougaloo to stand in for faculty there who wanted to go north for graduate study, and she refused any payment beyond room and board so that what would have been her salary could assist in that mission. She had a strong interest in Black Americans’ struggle toward educational parity and civil rights—scribbled notes in the archival collection for talks on the topic to students and alumnae suggest her usual careful research on this as on other topics. Her post-retirement work was a substantive contribution to the goal, giving the best she had to give.

Students at Mount Holyoke admired this teacher who, in Alan McGee’s words at a memorial gathering in 1976, “preferred ideas to come from the students’ own minds in the congenial atmosphere of discussion.” She wanted, McGee said, “to encourage spontaneity and courage in students’ thinking.” She knew how to guide students, even correct them, without ever “dispiriting” them – a too rare teacherly gift.

In addition, she was a leader on the faculty. McGee recalled her role, as Chair of the Academic Committee, in curriculum revision that was adopted in the year of her retirement. The new Basic Courses, he said, “encouraged an intellectual freedom which had not been possible in more traditional study. The Mount Holyoke student was permitted a degree of self-reliance and maturity unusual in the bachelor’s degree.” She established, in other words, a trend that continues to this day and from which we of the Class of 1960 clearly benefited; our distribution requirements may have been slightly annoying, but even today, far more nit-picky requirements can make students in some schools feel like they will never have time to pursue their own academic goals.

Writings by Griffith in the archival collection are few but striking in two common elements: meticulous thoroughness in research and a beguiling sense of humor whether the topic is Time Patterns in Prose, a tedious monograph published in 1929, or Horace: A Study in Popularity – The frivolous inquiry of a non-classical student, a talk to be given to Mount Holyoke students after time away on sabbatical leave. Her masterwork, if you will, was written in retirement and published locally: Dauntless in Mississippi: The Life of Sarah A. Dickey, 1838-1904.

Griffith was astonished at Tougaloo to come upon the portrait of a dignified white woman, who was, the attached plaque said, “our founder” and 1869 graduate of Mount Holyoke Seminary! Who was this woman, she wondered, and how did she come here? What did she do? Founder of what? Meticulous research again, in Mount Holyoke’s archives and around and about Clinton, Mississippi. The result of her work was a biography written with affectionate admiration. A flyer and order form circulated at the 1965 publication of Griffith’s book provides the best summary:

Among the heroic figures of the post-bellum south was Sarah Dickey, a Northern white woman who dedicated her life to the education of the emancipated Negroes. She first taught in Vicksburg in a mission school for her church, the Evangelical United Brethren, during the last nineteen months of the war. Returning north, she worked her way through Mount Holyoke Seminary, 1865-1869. Then, back in Mississippi, she taught in one of the first Negro public schools established by the Reconstruction government, lived in the home of a Negro, and withstood the attempts of the Ku Klux Klan to drive her out of the state. Indomitable, she held to her purpose of founding a school for young Negro women on the pattern of Mount Holyoke, and single-handed, she did just that.

An illustration in the book [of ten handsome black women] shows the class of 1897 at Mount Hermon Seminary, the name she gave to her school. Though nothing of Mount Hermon remains [whatever was left was subsumed into Tougaloo], Sarah Dickey’s story has considerable relevance for our time. In an era when racial prejudice was at its height, she gradually won for herself and her school the respect and gratitude of the town that had once ostracized her.

The last paragraph in the book illustrates what power and hope Griffith found in Dickey’s story and gives us a sense of the writer, her own steady faith in the possibility of enduring goodness in humankind:

How cheering it is to know that the change here recorded took place in the heart of Mississippi! Cheering also that this beneficent change centered in the life and work of a woman who accepted without reservation the statement that faith can remove mountains. That the mountain-movers raised up for her were fellow townsmen is perhaps the most cheering aspect of this case history, for what happened once can surely happen again. Sarah Dickey has blazed the trail. There are men of good will all through the South to follow it. The power of an individual must never be underestimated. The life of Sarah Dickey proves it.

The last chapter, so to speak, in Dickey’s life hold a little moral for us as we approach 2010! When Dickey’s classmates assembled in 1919 for their 50 th reunion (the same year, by the way, that Charlotte Haywood graduated and Viola Barnes joined the MHC faculty), the building of Clapp Laboratory to replace a science study center destroyed by fire was in process. The class of 1869, proud to have the largest proportion of living grads present in a reuning class, gathered funds to name a room in Clapp for Dickey. Contributions came from every living graduate of the class! $5000 for the Dickey memorial and $12,000 for the general fund, no small feat of fundraising for women of those times!

As for Griffith, she lived to the age of 94; her last years spent at a Quaker-sponsored retirement community in Pennsylvania. Evidence in the archives proves that her lively mind never shut down—she continued her tradition of composing sonnets for her Christmas greeting to friends to the very end of her days. After her 70 th birthday, the annual fourteen lines celebrated all the good fortunes of her life; the ending couplet noted the “greatest pleasure” of all:

It’s that of friendship. So, my friends, I send

My heartfelt thanks to you, a Christmas dividend.

Our thanks to Sara Dalmas Jonsberg who volunteered to research and write these biographies of two Mount Holyoke – connected women whose histories became intertwined.

February

Harriet Newhall

former Director of Admissions

born February 21, 1893 in Wilbraham MA

died March 29, 1973 in Springfield MA

I will tell you two stories about Harriet Newhall and me. I’m guessing that neither story will surprise you. In autumn of 1955 my high school principal and five seniors from Bourne High School left Cape Cod on a day trip and made the rounds of UMass, Smith, and Mount Holyoke in a big finny automobile. It was like sitting on your couch while going much too fast. I had never been so far from home. I knew about Mount Holyoke only because my father’s mother, who had an eighth grade education but was nonetheless a librarian at Yale Medical School, had a close acquaintance who had graduated from Mount Holyoke. I had an appointment to meet with Harriet Newhall. I was frightened nearly beyond speech.

Harriet Newhall attended Wilbraham Academy and Somerville MA high school, received her B.A. at Mount Holyoke in 1914, and first served the college as Assistant Secretary to the President, Mary E. Woolley (1915-16). Harriet took a year at Simmons College to secure a B.S., then returned as Secretary to the President until 1921 and became Assistant to the President from 1921-25. From 1925-27 she was Acting Secretary of the Board of Admissions. In 1928 she received an M.A. from Columbia University. In that year she returned to MHC to serve as Executive Secretary to the President. In 1937 she became Executive Secretary to the Board of Admissions, and from 1939 to 1958 held the title Director of Admissions. In 1950 she was promoted to the rank of Professor.

She served as advisor to the freshman class in 1947 and 1948 and was academic advisor to the classes of 1952, 1953, and 1954. She was elected Class Honorary by several classes, and in 1950 received the Alumnae Medal of Honor “for her humor and wisdom, sense and judgment, and that attractive quality of leadership that marks you as one of the foremost daughters of Mount Holyoke College.”

In a 1955 Quarterly article Harriet Newhall said, “I could tell you many stories about individuals who have been admitted—some as definite gambles, with most irregular entrance units, and examination scores that did not seem promising, but who came through with flying colors, as well as some with top scores, strong recommendations, and about whom there seemed to be not the slightest doubt of success, but who failed miserably. I will relate just one of our recent success stories……

Several years ago there was a girl who came from a small country high school in the Middle West, and when I say small, I mean small—a school of just over 100. She had never studied any foreign language, she could offer only 12 academic or acceptable entrance units instead of 16, and the record had to be stretched to find those 12, She had, however, led her high school class of 17 students for four years, made excellent scores in the the College Board tests, been active in school affairs, and was well recommended. She wanted to come to Mount Holyoke. There was considerable discussion in our meetings: Would it be fair to her to admit her with such an irregular group of units and rather sketchy preparation and foundation? Would she be able to do the work here and hold her own in the highly competitive academic group and in the completely different set-up?”

She continued, “We argued back and forth, but all were agreed that there was something about her that seemed to indicate promise, and she was admitted. She was well worth the gamble. At the end of the first year she ranked fourteenth in a class of 345, had won a special prize in English for a critical paper, and seemed happily adjusted. At the end of the sophomore year she ranked seventh in the class and was named a Sarah Williston Scholar. She had been active, too, in extra-curricular affairs. In the junior year she ranked fourth in the class, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa in that year… At the end of the senior year she was graduated magna cum laude, ranked fourth in a class of 280, and was a Mary Lyon Scholar. She was awarded a Fulbright, attended St. Hilda’s, Oxford,” and so on.

I had never been inside a college, never been in the presence of a truly elegant older woman. Stunned by everything in her office including the carpet, the desk, and Miss Newhall, I sat practically paralyzed in the handsome chair. After some pleasantries concerning Cape Cod and my high school, she asked me if I had read any of “the classics.” It wasn’t a trick question. I had read several of “the classics” but at that moment couldn’t think of the title of a single one. I was in white-out mode. Les Miserables suddenly came to mind. With a decent French accent I said it. The problem was that I hadn’t read it. My only conscious thought was that I’d never be accepted at Mount Holyoke. Miss Newhall asked me something straightforward about one of the characters; but nearly simultaneously she realized my predicament and gracefully transitioned to a different subject—as though she had had a better idea that was going to be more enjoyable for both of us. Grateful for her generosity and reassured by her kindness, I somehow found my voice.

She retired in June, 1958. In April of that year, during an interview with the Quarterly , she said with a smile, “Yes, I’ve had a rich, full life, but nobody should go into this work who isn’t a gambler at heart.” The element of chance had increased tremendously since she began admissions work. She went on to say that thirty years ago more than four-fifths of applicants to a college like Mount Holyoke wanted that college and no other. By 1958 admissions officers took it for granted that not more than half the accepted applicants would come. At a residence college located in a village, there was no margin for error in the living quarters. Each May, when the postcards from girls admitted for the next September came back, Miss Newhall watched each mail anxiously, haunted by the twin specters of an empty dormitory and ‘a trailer camp in South Campus’, the grim alternatives if she and the Admissions Board should have guessed wrong on the number of candidates accepting their acceptance.

One of the major rewards of admissions work, she said, is the “tremendously interesting people you meet.” She included first of all the 9,000 young women she shepherded into Mount Holyoke—and many of their fathers and mothers. Then there were the hundreds of school principals and guidance officers across the country whom she visited and consulted year after year. And her fellow admissions directors, particularly those in the other Eastern colleges for women who developed methods of mutual assistance in the midst of intense competition.

One requirement for an admissions director which had not changed in thirty years is a lively sense of humor. “And courage,” Miss Newhall added after a pause. She might also have mentioned stamina—the kind that, after a succession of days on the road, speaking to school assemblies, interviewing applicants, and describing college life at sub-freshman teas, enabled her to rush back to her hotel room to write up a deft personality sketch for each girl seen and still have zest for dinner at the home of an alumna, for joking with the husband, admiring the baby, playing with the cat.

From 1957 to 1960 she served as a trustee for the College Entrance Examination Board. She substituted during the 1962-63 academic year for the director of admissions at Wellesley College; and from 1963 to 1966 while living in Northampton worked on special projects at Converse Library and the Robert Frost Library at Amherst. She was a member of Phi Beta Kappa, the League of Women Voters, AAUW, and various professional organizations.

In 1972 Mount Holyoke announced the institution of a special tuition award to women graduates of Holyoke Community College. The Harriet Newhall Award opens up one place each year for a top student who, beginning in her junior year, enrolls as a non-resident student at Mount Holyoke. Tuition at MHC in 1973-74 was $2800.

The other story I want to tell is about Miss Newhall sending me a gift of money. Part of my financial aid package entailed having a noisy room next to the bathroom. It was freshman year; it was South Mandelle, where most of the rooms were singles. When I wasn’t studying I liked to leave my door open so people would be inclined to socialize on their way to or from the bathroom. I don’t remember anyone locking doors in those relatively innocent days. It was just before the holiday break and on top of my bureau I had a few gifts for my family and about $10 in loose bills for finishing Christmas shopping. That was it. When I went back to my room after supper, I saw right away that the money was gone. I felt sick. I’d been robbed by someone I knew; and I was broke. Within an hour there was a house meeting. Whoever took the money was given a chance to put it in an envelope with my name on the outside and leave it on a much-passed side table by morning. No questions would be asked and that would be the end of it. But the next morning didn’t bring the return of the money. What it did bring was an envelope in my mailbox from Harriet Newhall. Inside were a $10 bill and a letter. “Dear Miss Bradley,” the letter began, “There is a special fund at Mount Holyoke for assisting our students at a time like this. I hope that you will accept this gift. Best wishes for a wonderful holiday with your family.”

Now there was a woman for all seasons.

Sue Bradley Cabot (amitybc@maine.rr.com)]

March

Virginia Galbraith

Professor of Economics (and renowned economist)

March 28, 1918 – March 24, 1988

I met Ginny Galbraith on the first day of classes in the fall of 1953. As a freshman (first year), all faculty members looked old to me—but among the men of the Ec-Soc department, she was clearly YOUNG. It didn’t take long to learn from upper-class classmates that we were indeed fortunate. “She is the only one who can make curves understandable,” I was told. And they were right.

But stories about Ginny extended far beyond her teaching prowess. There were the stories whenever the other Galbraith (John Kenneth) came to dinner. No, they were not related; but they did flirt. Then there were stories of beaus from up and down the east coast. Fortunately, she moved out of Wilder into an apartment of her own in 1954. Otherwise, the stories would have extended to window entries for sure. I can vouch for the truth of at least one apocryphal story. She did, indeed, receive a bathtub full of roses for Valentine’s Day in 1955. My husband will swear to seeing them, as he used to hang out in her apartment when I was working on an independent project with her. They were all from one unnamed man and she maintained there was nowhere else to put them. Ginny had been married before she came to Mount Holyoke in 1950; she never married again, but she was never without a man in her life.

And then there were the worshippers from a distance. At some time in the early ’70s, Ginny came to New Haven to speak to the Alumnae Club about banking. The room was full of husbands who scoffed at the idea of a woman who was barely 5 feet tall telling them about banking. But tell them she did and the questions had to be halted when it was past closing time at the meeting location. Ten years later they were still talking about her. In the days when women economists were rare, she was the first female head teaching assistant at Berkeley, with eighteen men working for her. They were still rare in 1958, when she testified before the Massachusetts Public Utilities Commission (carefully dressed in hat and gloves). She was described by the Boston Globe as “probably the most attractive witness ever to testify as an expert economist before the Department of Public Utilities.” Joan Steiger reports that she had lunch with Ginny right after she testified and Ginny was VERY proud to have worn a “white sharkskin suit.” and wasn’t too embarrassed about the effect created when she crossed her legs in the slim, short skirt. She wooed the DuPont leadership into heavily supporting the program on Complex Organizations, of which she was a founder. Ginny knew how to use her feminism when she needed it, but in the end it was her mind that impressed.

I thought I knew how to write when I met Ginny. After all, I had been editor of my high school paper and worked for the News Bureau at Mount Holyoke. I quickly learned otherwise. Ginny was a writer and she brooked nothing but the best. She demanded that I write, as she taught – concisely and clearly. I remember the costs curves, and the economics has stood me in good stead, but the most important skills I learned from Ginny were to write and to teach. In 1976 I was her teaching assistant in the Complex Org Financial Analysis course. The class had an equal number of Amherst men and Mount Holyoke women. It was clear on day-one that the boys (I use that term intentionally) thought they had it easy; they were going to dominate the class. Ginny and the Holyoke women disabused of that idea quickly.

Ginny remained at Mount Holyoke until she retired in 1983. But her professional career extended to training managers as well as college students. She served for many years on the Board of the Arthur D. Little Management Training Institute and for six years trained management personnel in African, Asian and Latin American under-developed countries.

Among my favorite “Ginny stories” is one she told about an event that happened one summer at the University of Minnesota, where she was doing some work. She heard a student knock on the door of the faculty office across the hall from her office every day for a week. And every day the faculty member said “I’m busy, come back anther time.” Finally, when she heard the student in the hall, she stepped out of her office, crossed the hall and knocked on the door in his stead. When asked who is it, she replied “It’s Ginny.” In response to “Come in” she opened the door, pushed the student in, shut the door and returned to her office.

Then there was the house on Greenwood St., all glass and steel and filled with African masks. Eat your hearts out—it was built for $15,500, won architectural awards and was featured in House and Garden. It was exactly Ginny—one large airy room to share with friends and students, one small room to sleep, a wall kitchen that could be covered with folding doors from which she could produce ANYTHING.

Ginny loved France, and some years before her retirement, built a house in Duras, a small town in the Bordeaux region. Because Americans could not own property in France in those days, she arranged for the house to belong to the Mayor of Duras, who was also the butcher. The house overlooked the rolling hills that surrounded the medieval town and the patio was perfectly sited for that late afternoon glass of wine before dinner. In the years before her retirement, she rented the house to an American artist in the winters. As proof that there are only forty people in the world and the rest is done with smoke and mirrors, I met that artist years later and we shared our love of the house and its site. But my fondest memory of visiting Duras after Ginny retired there was standing in front of the TV in the Mayor’s house arguing French politics in French. I don’t think Ginny or I convinced him of anything.

Ginny’s life in Duras was cut short and by early ’89 she was in Holyoke Hospital with breast cancer. But she was still Ginny. Several of us who visited her regularly never saw her without makeup. When she lost her hair, she had a proper wig, penciled eyebrows, lipstick and a smile.

She was a role model and mentor for many of us.

P.S.

Sandy Germond Pritz adds:

Miss Galbraith was the professor from whom I needed to gain approval when I decided during the summer after my sophomore year that I wanted to major in economics rather than the discipline I had previously declared. I started by revealing that I had never had a course in economics, but had only gone to one lecture with my roommate the previous spring and felt drawn to the subject – hardly a basis for changing my major, most might think! However, Miss Galbraith was openly inviting and friendly, and I remember she focused on what I was saying even while patting her never-astray hairdo, which I came to see as one of her endearing mannerisms. Her serene confidence was reinforcing, even though her courses were challenging. She not only accepted me but subsequently became my honors advisor in economics. I remember her very fondly!

April

Frances Perkins

April 10, 1885 – May 14, 1965

(https://www.mainepublic.org/post/frances-perkins-life-and-legacy-fdrs-secretary-labor-relevance-her-work-today. Added October 21, 2020.)

A 1902 graduate of Mount Holyoke, she was an aristocratic progressive who retained her maiden name after marriage. She joined the settlement-house movement, working at Hull House and becoming an advocate of social reform, with a particular interest in the problems of blue-collar workers. In 1910 she received an M.A. in social economics from Columbia University and began serving as secretary of the New York Consumers League. In that position she investigated conditions in factories, especially those employing women and children, and lobbied for the reduction of their workweek.

During Roosevelt’s governorship (1929-1933) Perkins headed the state industrial commission. As President, Roosevelt appointed her Secretary of Labor. The first woman cabinet member in U.S. history, Frances Perkins and her post became a lightning rod for criticism and attack by the many business, labor and political opponents of the New Deal. Perkins proved equal to the task and administered her expanded duties with notable efficiency and restraint, withstanding repeated private and public attack. During her tenure she strengthened an almost defunct department, injecting new life into its bureaus of Labor Statistics, Women, and Children. She spearheaded enactment of the Social Security Act of 1936, was committed to federal public works and relief, and championed legislation for minimum wages and maximum hours and for the abolition of child labor.

The desperate conditions of German Jews under the Nazi regime moved Perkins to help. Beginning in April 1933 she made it a primary cause. She stood alone in Roosevelt’s cabinet as an advocate for the liberalization of immigration procedures, boldly confronting the Secretary of State and his deputies when trying to find ways and means to enable as many Jewish refugees as possible to enter the United States. Her advocacy was essentially doomed, in the main by anti-Semitism.

On Perkins’s death, the Times of London praised her as “one of the chief architects of the New Deal,” a woman with a “true sense of justice and humanity.”

To learn more about this strong woman, to whom we all owe much, read this excellent biography: The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life and Legacy of Frances Perkins, Social Security, Unemployment Insurance, by Kirstin Downey.

May

Meribeth Elliott Cameron

May 22, 1905 – July 12, 1997

Recently, Fran Hall Miller wrote, “Well I sure remember a line Dean Cameron delivered at Orientation in 1959 and it was, ‘You study the liberal arts to save yourself from middle age.’ I hadn’t a clue what she meant then, but the phrase stuck with me, and I sure know what she meant now. I also remember that she told us that if we were ever in trouble (on a date?) we should call her, day or night, and she’d come and get us. My mental picture of her ever after was of a lady with black hair back in a bun driving up to ‘get me’ somewhere in the middle of the night, dressed in a granny gown and nightcap, carrying a candle.”

At that time, Meribeth Cameron was only 55 years old! Ten years later she was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws by President David Truman who said, “The College is proud to recognize the achievements of a truly remarkable woman. A respected scholar, beloved teacher, able administrator, and wise and witty human being, Meribeth Cameron has left an indelible impression on the institution which she has served so well for twenty-two years. Although she has never been associated with the Women’s Liberation movement, its adherents could well take vicarious satisfaction in her accomplishments [for] how many women serve as college presidents, top educational administrators, and presidents of international organizations and reach the rank of full professor in a highly competitive field? She is living proof that intelligence has no gender.”

Ms. Cameron was born in Ontario, Canada. She attended Stanford University, obtaining her BA in history in 1925, an MA in 1926 and a PhD in history and political science in 1928. Before joining the Mount Holyoke College faculty in 1948, she taught at Stanford University, Reed College, Flora Stone Mather College of Western Reserve and was Dean and Professor of History at Milwaukee-Downer College. Her area of specialization was Far Eastern history. She joined the faculty of Mount Holyoke as Academic Dean and, as such, served on most of the major committees of the College while also teaching a course on the History and Civilization of Eastern Asia. She is said to have had no faculty enemies. In addition she served as acting president of Mount Holyoke in 1954, 1966 and 1968-69, the last following the resignation of Richard Glenn Gettell. (1) In 1954 and 1966 she served as Academic Dean while she continued to teach her course; during this period in 1966 she was also chairman of the Four-College Committee on Asian and African Studies. (Mary Lyon would have been proud of her ability to multi-task!)

From 1959-1962 she served as President of the International Federation of University Women, a diverse organization with member associations in 55 countries. One of these organizations was the American Association of University Women of which Dean Cameron was a member of the Board of Directors and Chairman of the National Committee on International Relations. As part of her work for these organizations, she attended planning sessions and conferences throughout the world.

Ms. Cameron is the author of “The Reform Movement in China, 1898-1912” and co-author of “China, Japan and the Powers”; she has written many articles and reviews and has edited a number of journals. She holds four Honorary Degrees and she is an honorary member of the Mount Holyoke College Alumnae Association. She was a member of the Massachusetts Advisory Commission to the United States Committee on Civil Rights and has served on Institutions of Higher Education of the New England Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools. In a release to the New York Herald Tribune in 1949, she said, “It is too late to save the Nationalist forces in China, and they probably could never have been saved by foreign aid anyway…an all out aid from the United States to the Nationalists might well invoke active Russian participation in the Chinese crisis and bring on WWIII…The Chinese Communist movement is not a recent Russian conspiracy but is a ‘Chinese Revolution’ which started decades ago. For us to view the Chinese revolution as a mere episode in our contest with the USSR is short-sighted. The American people must become better informed about the origins of the revolution so that, as it progresses, we can support policies which are not opportunistic and short-range.”

In 2006 a fund was endowed in honor of Meribeth Cameron. This prize is awarded to two faculty members for excellence in teaching. It was endowed by Janet Hickey Tague, 1966, who remembered the Dean as “a formidable, intellectual presence on campus.”

In 1981, ten years after her retirement, Dean Cameron reported: “I find retirement a blessed condition. I have traveled…written a couple of articles, reviewed many books for professional journals, and made a few speeches. I read widely to make up for all the years when I despaired of having the time to even open a book. I enjoy music…and, to my surprise, I watch birds!” Granny gown, indeed? Are “we” finding retirement to be a “blessed condition?”

(1) An interesting article in the Harvard Crimson in October, 1958 discusses the speech by Richard Glenn Gettell in which Mount Holyoke and the ‘Uncommon Woman’ are defined. Dean Cameron is quoted liberally describing the honor’s program and compares it to that at Harvard. Sources: Papers in the Archives

Kate Bracher has this addition to make to the biography on Martha Hazen released in August:

“In addition to her (Hazen’s) distinguished professional career as an astronomer, she taught at Mount Holyoke College for two years, 1957-1959; I think this was just before she finished her PhD at Michigan. She left Mount Holyoke to marry Bill Liller, her first husband and a fellow astronomer. I took a couple of courses from her, including astrophysics, and she was one of the people who (by example) made it clear to me that women could do astronomy. I used to see her occasionally at astronomical meetings, and she was always glad to see me and to see one of her students being a successful professor of astronomy. I enjoyed knowing her, and was very sorry to hear of her death.”

May (2)

May 8, 1893 – March 27, 1993

(model for Wonderwoman)

MHC 1915

In the most recent class letter, we asked that you comment on your own process for “managing the archives.” Research on the woman we chose to feature for May confirms that this has been a familiar problem for decades, indeed, forever. In 1970 Elizabeth wrote:

“As of this moment I am doing what everyone else in the class has done years ago—getting rid of papers, journals and such that shouldn’t be left around for someone else to handle.” She continues, describing scrapbooks, photo albums and a compilation of her husband’s illustrious career. “I am trying to put my house in order—about time at 77—to paraphrase Milne, ‘an extraordinary age for so young a person to be.’

Elizabeth grew up in the Boston area but she was born Sarah (Sadie) Elizabeth Holloway on the Isle of Man while her parents were on summer vacation.

Fast forward a number of years… years where independence was encouraged by both parents…years she spent at Mount Holyoke, graduating in 1915 with a BA in psychology; and then, “Those dumb bunnies at Harvard wouldn’t take women so I went to Boston University.” She graduated Law School in 1918.

During this period she had kept an ardent suitor, William Marston, waiting. They were married in 1919 and she continued her education after her marriage, completing an MA in Psychology at Radcliffe. In addition to having a law degree and PhD in psychology from Harvard, her husband wrote and worked for Universal Studios, applying psychology to every branch of the activities of the Studios. [This was truly a power couple]. In 1929, the Mount Holyoke Alumnae Quarterly contains the following written by her husband: “It occurred to me that her friends ought to know she is still on deck. Do you know that Betty…was managing editor of Child Study Magazine…wrote many interesting and successful trade articles and ‘broadsides’ for the Policy Holders Service Bureau Metropolitan Life Insurance Company…left to become a member of the Editorial Department of the Encyclopedia Britannica, handling psychology, anthropology, medicine, physiology, law and some biology?…worked as editor and wrote an article on ‘Conditioned Reflex’ to appear as a signed article in the Britannica—until August 28, 1928, when she had…a son?…that she has been doing graduate work at Columbia in Psychology for her PhD?..that she collaborated very largely with her somewhat soft-witted husband in writing ‘Emotions of Normal People’…and is now co-author of a general psychology to appear next fall…that she has been an instructor in Psychology at Washington Square College in N.Y.U. for a couple of years?…that she is the best wife and mother who ever lived in addition to her outside activities? There is something for your flyer, Miss Voorhees.”(1) Her editorial comment is: “Do we see other husbands seizing their pens?” Our editorial comment would be that during this time, a young student of Marston’s, Olive Richard Byrne, moved in with the couple and they lived openly in a polyamorous relationship, both women bearing him two children. Olive’s children were formally adopted by the couple.

In 1937, Elizabeth wrote that she is a “‘working mama’ which means a job all day and four children all the other waking hours…We eat buffet suppers en masse or cook wienies in the orchard fireplace…with usually about ten children and a dozen or so adults.” The two combined psychological insights to write about the physiology of deception and they developed a crude polygraph machine which they never marketed. She indexed the documents of the first fourteen sessions of Congress, lectured on domestic relations, commercial law and ethics in addition to the accomplishments listed above.

Before creating a new cartoon character in the 1940’s, her husband consulted with her evoking the comment: “Come on, let’s have a Superwoman! There are too many men out there.” He used his wife, a truly ‘liberated woman’, as the inspiration for the character of Wonderwoman , a superheroine, living on the Isle of Paradise who entered our violent dimension to combat the aggression of history’s males through the Amazon philosophy of love and strength. “SHAZAM!” His character promoted “global psychic revolution” through the use of non-violence by forcing evil doers to look into their own hearts where some good always resides. Wonderwoman continues to battle “prudery, prejudice, sexism, crime, hatred and racism with the Power of Love.” William died in 1947. The women remained together until Olive’s death in the late 80’s.

Later in life, Elizabeth communicated regularly with Mount Holyoke, providing address changes and inquiring about classmates. Several of these letters were answered in an affectionate manner by Carolyn Berkey, Executive Director (2). In 1985 Elizabeth attended her 70th Reunion and wrote to compliment Allen Bonde who played the piano at a dinner which Carolyn had been unable to attend. Carolyn assured Elizabeth that Allen would continue to play at the Loyalty Reunion every year as long as he was willing and then advised her of the whereabouts of one of her classmates, assuring Elizabeth that she was doing fine. For the last three years of her life Elizabeth lived with one of her sons; she died at the age of 100. Wonderwoman, as they say, lives on!

____________________________________________________________________

(1) Helen Voorhees also graduated in 1915. She worked as Assistant to Dean Purington at Mount Holyoke and was later in charge of career counseling, writing about the employment picture for college women from 1929 until the Post-WWII Period. She was a contemporary of Harriet Newhall; they worked together and have been honored together.

(2) Carolyn Berkey served the College in many ways. Besides being Executive Director of the Alumnae Association, she worked in the Development Office. She was the wife of Robert Berkey, Professor of Religion.

Sources:

Archival Files and Papers

Wikipedia and…We thank Fran Hall Miller for suggesting this candidate to us.

June

VIRGINIA APGAR

June 7, 1909 – August 7, 1974

Dr. Selma Calmes has said of Virginia Apgar “She drove her convertible like an airplane. Once she took off, the wheels seemingly never touched the ground.”

Virginia graduated from MHC in 1933 and attended Columbia Medical School. After being advised (by a male colleague) that she should not continue in surgery, she turned her attention to anesthesiology, a fledgling field at the time. We all recognize her as the originator of the Apgar score for ranking newborns; this was presented in 1952 and is still considered to be the best predictor of infant health in the first month of life. Her “prepared mind” is cited for her ability to devise this score so spontaneously. She was not considered for chairmanship of her then male dominated department, but continued to practice anesthesia and champion interest in perinatal care (maternal and infant) and infant resuscitation.

When she was 50, she earned a master’s degree in public health and became Director of Research and Development for the March of Dimes. She fostered national awareness of the, previously taboo, subject of premature birth.

She was an accomplished cellist and violinist. She was so committed to musical excellence that she fashioned her own stringed instruments. Musicians have given concerts in her honor using these instruments and it is the hope that they may be purchased and donated to Mt. Holyoke.

A commemorative stamp was issued in her honor in 1994, and in 1995, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. She was given an Honorary Degree by MHC in 1965. An emeritus MHC professor recalls that she frequently visited the college and was encouraging and helpful to premedical women even in her later years. We like to think that her MHC education contributed to the “prepared mind” cited for her many achievements.

She said: “Life is a celebration of passionate colors!

Act promptly, accurately and gently.”

….more good advice from a powerful, pioneering woman….

July

Elizabeth M. Boyd

Professor of Zoology

July 8, 1908 (Liverpool, England)

January 23, 2006

Upon reading Bessie Boyd’s obituary in the newspaper, classmate Joan Corcoran Steiger wrote, “It has been a day to reflect on Bessie Boyd. I never took one of her classes, but we became friends in Leningrad in 1976. We attended a ball in the Hermitage; wore our most elegant gowns and priceless jewelry as we glided down the marble staircase, acknowledging all the crowned heads of Europe gathered to honor us. At least that is what we pretended to do. My gown was a dark green taffeta; hers was even more beautiful because she had a better imagination. Once was not enough; I lost count of the number of times we went to the second floor and gracefully descended. Our object was to feel as regal as possible and NEVER look down. We got to be pretty darn good at it too! I thought Bessie was frightfully old to go along with my little-girl-playing-dress-up approach to the palace, but now I find that she was then the age that we are now!”

When interviewed after her retirement in 1973, Professor Boyd said, “Retired yes, but now Retreaded.” Although she had moved to Florida, she returned to South Hadley every spring to participate in a program called Focus: Outdoors, a Nature, College conference which was held on Campus during the 1970’s and 80’s. (She was chairman of this conference when Roger Tory Peterson, a famous naturalist, lectured and exhibited his paintings on Campus.) She continued to give occasional lectures at a number of colleges, did hospital volunteer work, participated in Mount Holyoke Alumnae activities, and gave travel lectures. In 1982 she was a leader on the Mount Holyoke College Alumnae trip to the Galapagos Islands. Rumor has it that she had quite accurately demonstrated the mating dance of the Blue-Footed Booby to her classes for years prior to this. As a dedicated ornithologist, she was an active leader in the Massachusetts Audubon Society. Friend and colleague, Kay Holt affectionately recalls times that they played golf together. At that crucial moment of silent concentration when serious golfers contemplate their stroke, Bessie was very apt to loudly call attention to a bird flying overhead!

Bessie Boyd was a Scotswoman who was denied a medical education in her own country. She came to Mount Holyoke to obtain her master’s degree and returned (after earning her PhD in bird parasitology at Cornell) to teach zoology from 1937-1973. Susie Beers Betzer ’65 says that she was the professor who changed her from a French major to a zoology major, launching her on a career of oceanography and, eventually, medicine. Bessie’s file includes many letters of praise from her students and because of this; we can truly believe that she practiced what she wrote for Llamarada 1965: “The responsibility of faculty members at Mount Holyoke and our relationship with students differ basically in several respects from those at Universities. TEACHING undergraduates is our most important role; conducting graduate work and research are of secondary importance…promotion is not based on output of publications. Our method of teaching is to guide the individual student to think for herself. We encourage her to select a good liberal arts program, so that she may become an interesting and understanding person of sound integrity and judgment prepared to adapt to new environments and to serve as a useful and valuable citizen…”

Professor Boyd was the last active professor who had been appointed by Mary Woolley. She recalled that in the fall of 1931, the College opened one week late due to an epidemic of infantile paralysis. The foreign students had already begun their journey by ship and could not be contacted. When they arrived, they were all housed in Safford making a memorable transition week. At Commencement in 1932, Miss Woolley spoke to the class by radio broadcast in Chapin. “It was quite thrilling!” Boyd said. Miss Woolley returned from the Geneva Convention in the fall of 1932 and,” the entire college lined College Street (both sides), like greeting the British Royal family, we waved and yelled our greetings.” Following a hazardous trip to Edinburgh when Britain was at war with Germany, Boyd helped establish the MHC British War Relief Fund. It was during WWII that admission was first charged for Faculty Show and half of these proceeds were sent to the American Red Cross. During the time of student unrest in the 1960’s, Bessie encouraged the faculty, including President Truman, to institute a special chapel service in memory of those killed at Kent State. Having lived through Armistice Day in Britain where it was “business as usual,” she hoped to avoid the policy taken by other Universities, that of closing down the College. She was, indeed, a dedicated scientist who described 15 new types of bird parasites. Both a species (Sternostoma boydi) and a genus (Boydia) have been named after her. When awarded the Alumnae Medal of Honor, her citation read, “Thanks to your personal efforts, the Acadia Wildlife Sanctuary can boast of improved permanent facilities. Perhaps even more of us have admired your diligence and stamina over the years in organizing groups to seek after birds whose hours of rising pose a challenge to the more sluggish habits of Homo sapiens….” She was a vigorous champion of the benefits of Sabbatical years citing her experiences after leaving masculine environment of Edinburgh which gave her confidence in herself. She said that she was “a living example of the need for the retention of women’s colleges such as Mount Holyoke.” YES!

We know many women still feel this way as the number of applicants to Mount Holyoke continues to rise annually. I wonder if any of us can accurately recall exactly why we chose to come to Mount Holyoke. Memory does re-invent itself.

July (2)

Mary Emma Woolley

July 13, 1863 – September 5, 1947

“How uncomfortable to be a static female in a world where all the males are moving.”

Mary Emma Woolley agreed with Epictetus who said, “To live in the presence of great truths and eternal laws, to be held by permanent ideals; that is what keeps a man patient when the world ignores him and calm and unspoiled when the world praises him.” Biographies attest to Ms. Woolley’s patience and calm as she administered this Institution.

The first female to graduate from Brown University, this energetic, visionary woman taught at Wellesley before becoming President of Mount Holyoke from the turn of the century until her retirement in 1937. Inside the College, she fostered an orderly, forward looking program.

She instituted broad measures of academic freedom, both within departments and in an individual’s working day. Endowments improved, equipment was updated, and she encouraged interdisciplinary learning. She felt that it was “long overdue for scientists to communicate with non-scientists”.

She established more democratic conditions, encouraging equality of opportunity and diversity, and she increased faculty salaries. She was a NON-denominational President. Outside the College she stood for “whatever concerns the welfare of women, the advancement of education (and broader interests for women), and the conservation of young life.” This, of course, included being a spokes person for women’s suffrage. Active in the cause of world peace, she strongly believed that women could be helpful in the peace process. She was the only woman chosen from the United States to be a delegate to the Geneva Disarmament Conference in 1932, which she attended during her Presidency.

It has been said that Ms. Woolley had “a personal immunity to panic.” She was an attentive woman who was never bored and who loved the out-of-doors. She was partnered to Jeanette Marks, an English professor at Mount Holyoke, for 52 years. Ms. Marks wrote a biography of Mary Woolley.

She believed that building character was one of the main objects of education and that college should provide young people with a “broad mental culture while preparing them to earn their own living.”

She emphasized that education gave purpose to life and she differentiated between achieving and education, feeling that an education is extremely important in the management of a home, for a woman could gain a truer “perspective” which afforded her more tolerance and understanding.

She lectured that this allowed one to understand that hopes and dreams are not confined to those who have the opportunity to gratify them. An educated woman could pass these philosophies on to her children. “Perspective”, to her, implied “poise” or self-possession and her writings state that the “control of self” should include thoughts of “steadiness, balance and serenity.” During her years as president, polls of college students stated that one of the most important things they learned was self control for they felt that this enabled them to adapt and maintain serenity. She concurred with Martineau who said, “The soul occupied with great ideas best performs small duties.”

Ms. Woolley did not believe that knowledge alone was power but that this knowledge without the ability to “concentrate the mind” was virtually useless. She lectured that “acquirement and training become a means to an end rather than an end in themselves.” These factors, she said, serve in the development of power which is the secret of effective service and peace and happiness.

To apply the knowledge we acquire….. the power of critical thinking….. acceptance of diversity….. the avoidance of “whatever-ism”….. calm….. the legacy continues…..

August

Carolyn Berkey

Executive Director of the Alumnae Association

Development Office

August 9, 1931 – February 8, 2007

At Commencement weekend in 1982, Alumnae Association Executive Director, Carolyn Berkey was admitted to “Honorary Membership in the Alumnae Association of Mount Holyoke College, with all its rights and privileges.” This was met with a round of vigorous applause for she was said to have “guided the staff with creative vision, inspired enthusiastic participation of volunteers, augmented the stature of the Alumnae Association in the College community and gained the respect and affection of all those who have worked with her.” She was, indeed, instrumental in achieving the world-wide birthday celebrations for Mary Lyon’s birthday which helped produce national and international acclaim for Mount Holyoke when the Associated Press ran the story. Television viewers also saw a member of the “Today Show” wear a Mount Holyoke sweatshirt during the first celebration. (Since this time I have heard that Bill Cosby has also worn one on his TV show.)

Who was this non-Alumna who became the Executive Director of “our” Association, making her responsible for implementing the programs of the (then) 23,000 members and working with the volunteer board of directors and committees to “create and continue the variety of activities which support the interests of Mount Holyoke?” She came to Mount Holyoke in 1958 as a young wife and mother when her husband, Robert Berkey, accepted a position as professor of religion. (Retired 1999/ Died in 2006) We are told that her home became a “gathering place and haven for students seeking counsel, inspiration and renewal.” Using her master’s degree in religious education she served the community as executive director of the Holyoke YMCA and as a volunteer in the South Hadley Congregational Church. She joined the staff of the Development Office at Mount Holyoke in 1973 and became head of annual giving where she “inspired countless alumnae to new heights of financial support and dedication.” She was appointed as Executive Director of the Alumnae Association in 1980, retiring in 1988 in order to accompany her family to England on Sabbatical. During her tenure, she had made an effort to reach alumnae in many countries both when she visited privately and on Alumnae Association sponsored trips. It was said that “programs burgeoned in creative content and scope reaching throughout the country and around the world.” For these things she received the Alumnae Medal of Honor.

Carolyn was born in Egypt to missionary parents and she returned much later to teach English there. She was an “Egyptologist” but her true love was England. She traveled extensively; she loved Art; she did brass rubbings; she loved music and poetry. It was fitting that a favorite poem of hers by Emily Dickinson was read at her memorial service:

The Bustle in a House

The Morning after Death

Is solemnest of industries

Enacted upon Earth,

The sweeping up the Heart,

And putting Love away

We shall not want to use again

Until Eternity.

When I (Dana) moved back to South Hadley in 2002 and became acquainted with Carolyn Berkey, I was impressed by her grace and contagious enthusiasm. She seemed to have boundless energy as she traveled with her grandchildren and continued to respond to any community need with warmth and joy that endeared her to everyone including me; a newcomer! Indeed, she and I were in the early stages of planning a trip to the Galapagos Islands with our respective young granddaughters. While spending time in the Archives collecting material for these “Birthday Biographies,” I read many letters from Carolyn which had been written to countless (featured) alumnae during her tenure. She responded to what seemed to be the most minimal query. It might have been a request from an older alumna about a classmate or a change of address or a procedural question or an opinion about a policy as well as an enthusiastic response to a reunion that alumna had just attended. To an older alumna concerned about the possible death of a classmate she wrote that, indeed the person in question had just visited another classmate in Florida so that she was “fine and traveling” only a month before. She had extensive communication with Elizabeth Halloway Marston (aka “Wonder Woman”, see above) during her later years and they read as letters to an old friend. She responded in a gracious fashion to alumnae of all ages. Her responses referenced each question and they were answered with palpable warmth and a sense of caring that tended to make one feel valued by the Institution she represented. She was, indeed, an expert at communication, an uncommon woman and an ambassador for Mount Holyoke College.

September

September 15, 1865 – January 8, 1935

In 1893, Toshi, (aka Martha Gulick), was the first woman of Asian descent to graduate from Mount Holyoke College. In response to the notification of her 25th Reunion in 1918, she wrote, “Since I am so far away, I cannot have the pleasure of seeing you.” She was eager to see old friends but conditions for travel were not permissive.

Toshi, of Chinese birth, was abandoned as an infant in North China. The infant’s father spent his life mining coal and her mother was forced to labor long hours. A missionary couple, Mr. and Mrs. John Gulick, had recently lost a child at birth and readily took on the care of the newborn, Mrs. Gulick discovering that she was even able to nurse her. (1) They took the infant to Japan. As she grew up, she often accompanied her parents on horseback as they made their missionary journeys. Mrs. Gulick had visited Mount Holyoke in 1872, at which time, despite the fact that she herself was English, she began to “cherish the hope” that her daughter might be educated there. Toshi’s early schooling began in Tokyo in the American School for Girls and she was a member of the first class to graduate from Kobe College in 1882. Arrangements were made for her to attend Mount Holyoke but before she departed on the long voyage, she became a Japanese citizen . She studied at Mount Holyoke from 1890 to 1893.

A letter describing her trip home indicates that she stopped to visit the “Dickinson girls” and then proceeded to Oberlin College, Chicago, Winnipeg and Vancouver. She writes of the Fair Grounds in Chicago with the “night illuminations being very fine…” “It seemed so wonderful to think how all these things were brought from all parts of the world!”

Upon her return to Yokohama she taught at Kobe College and was one of the outstanding teachers of English to her own people. She married the Reverend Yoschimichi Hirata and they had five children, two of whom died in infancy. She became an enthusiastic helper in the Church. Her home was destroyed in the earthquake of 1921 but she was not injured.

In a letter to the College, she says, “I wish my students appreciated Shakespeare more. They think he speaks too much of love and so he is not good for young boys and girls to read.” She continues, “I am so glad to hear that the girls have a beautiful reading room, but don’t you wish the glorious ’93 could gather once more in that old lecture room and fight our battle o’er again? You do not know how your letters make me wish we were all together again at Mount Holyoke and digging again through the gold lay deep in the mountain.”

Chinese by birth, Japanese by citizenship, with a British mother, and an American father, Toshi was truly an International student who appreciated her connection to the Mount Holyoke community.

Much has changed since 1893. Current statistics indicate that in 2007 there were 266 Asian-American students enrolled. Also in 2007, there were many of Asian citizenship at Mount Holyoke. The breakdown was as follows: Bangladesh: 11, China: 50, India: 21, Japan: 8, Korea: 1, Nepal: 22, Pakistan: 17, Philippines: 1, Singapore: 2, South Korea: 18, Sri Lanka: 6, Taiwan: 1, Thailand: 2, Vietnam: 12.

(1) “Who’s Who” describes John Gulick as born of American missionary parents in Hawaii. He worked as a miner in California, graduated from Williams College and attended Union Theological Seminary. He married in 1864 but I was unable to discover anything about his English wife. He was a missionary in Kalgen, China before going to Japan from 1875-1899. He wrote a great deal about Darwinian topics.

October

October 11, 1884 – November 7, 1962

“No one is neutral about Eleanor Roosevelt. I know people, reasonable folks, who loathe even her memory. To countless others, the former First Lady is the jewel in the crown of the New Deal, a heroine who changed forever the notion that Presidential wives are mere adornments. ‘If democracy had saints’, said Adlai Stevenson, ‘Eleanor Roosevelt would be the first canonized’.”(3)

ER visited Mount Holyoke five times, staying at the College Inn and at least once in a dorm, discussing with Mary Woolley women’s role in the peace process (a favorite topic of Woolley), and in October of 1945 lecturing at Chapin to an audience of 1200 (1) on “Politics in a Democracy.” ER first visited MHC in 1931, when her husband was Governor of New York. During her 1945 visit, she said she planned to make several public appearances that fall in the interest of the Political Action Committee of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (1)—to some, including my own rural Republican parents, known as the dreaded CIO.

She also declared herself in favor of a year’s compulsory training for both boys and girls. In answer to a question from a student, she said, “I would be opposed to a year devoted to military training for boys alone. If we have military service, I hope it is for boys and girls alike. I hope we discuss fully what kind of training and what kind of service is to be accomplished in that year.”

She said that the United States citizen must care what happens to all the peoples of the world “for purely selfish reasons….. [because] what happens to them will affect our economy.” Her lecture emphasized the importance of the individual’s education in a world so closely knit. “It is really very frightening.” In discussing education in a democracy, ER said, “I hope that this challenge is going to be met. Otherwise I see only misery, apprehension and fear in our generation and in the coming generation. And in the end I see only destruction.”(1)

After the MHC lecture, she took questions. “She takes that period with great understanding,” wrote the Holyoke reporter. “In the first place she knows her answers or she says with utmost frankness, ‘I don’t know’. It is very refreshing to have somebody say that to a questioner.” (1)

Her most recent biographer, Blanche Cook, recalls ER visiting Hunter College in 1961, when Cook was a student and ER was a student advisor. When the regally tall Mrs. Roosevelt entered the room, the atmosphere changed: “So much energy bounced off her. And I remember her eyes—they were an incredibly clear, luminescent blue.” (2)

Goodwin writes, ‘Eleanor shattered the ceremonial mold in which the role of the First Lady had traditionally been fashioned, and reshaped it around her own skills and her deep commitment to social reform. She gave a voice to people who did not have access to power. She was the first woman to speak in front of a national convention, to write a syndicated column, to be a radio commentator, and to hold regular press conferences’. (5)

She had been propelled to that place of prominence by her strengths and resourcefulness. Thirteen years after her marriage in 1904, and after bearing 6 children, Eleanor had resumed the search for her identity that had been interrupted by being orphaned at 10 and married at 21. ‘The voyage began with a shock—the discovery in 1918 of love letters revealing that Franklin was involved with Lucy Mercer, Eleanor’s personal secretary. “The bottom dropped out of my own particular world,” she later said. “I faced myself, my surroundings, my world honestly, for the first time.” There was talk of divorce, but when Franklin promised never to see Lucy again, the marriage continued. For Eleanor, a new path had opened, a possibility of standing apart from Franklin. No longer would she define herself solely in terms of his wants and needs.

Long before the contemporary women’s movement provided ideological arguments for women’s rights, Eleanor instinctively challenged institutions that failed to provide equal opportunity for women. As First Lady, she held more than 300 press conferences that she cleverly restricted to women journalists, knowing that news organizations all over the country would be forced to hire their first female reporter in order to have access to the First Lady.

Nowhere was ER’s influence greater than in civil rights. Citing statistics to back up her assertion that blacks were being systematically discriminated against at every turn, she confronted her husband relentlessly, barging in to his cocktail hour and cross-examining him at dinner. She compelled him to sign a series of Executive orders barring discrimination in the administration of various New Deal projects. African Americans’ share in the New Deal work projects expanded, and Eleanor’s independent legacy began to grow. Her positions on civil rights were far in advance of her time: ten years before the Supreme Court rejected the “separate but equal” doctrine, Eleanor argued that equal facilities were not enough—”The basic fact of segregation, which warps and twists the lives of our Negro population, [is] itself discriminatory.”

She understood the importance of symbolism in fighting discrimination. In 1938, while attending the Southern Conference for Human Welfare (which she had helped found) in Birmingham, Alabama, she refused to abide by a segregation ordinance that required her to sit in the white section of the auditorium, apart from her black friends. The following year she publicly resigned from the Daughters of the American Revolution after it barred Marian Anderson from its auditorium.

During WW 11, Eleanor remained an uncompromising voice on civil rights, insisting that American could not fight racism abroad while tolerating it at home. Progress was slow, but her continuing intervention led to broadened opportunities for blacks in the factories and shipyards at home and in the armed forces.

She never let the intense criticism she encountered silence her’.(5) ‘She was unstinting in her commitment to Arthurdale, the federally planned housing community in West Virginia, and to providing health care for all Americans. Thumbing her nose at convention, ER opened the White House to women reporters, to African-American activists including Mary McLeod Bethune and Walter White, and to labor zealots such as Georgia’s Lucy Randolph Mason. For all this, of course, ER suffered the slings and arrows of virulent critics, many from the white South, but also Yankee Republicans who deeply resented her activities.

She spoke out for federal anti-lynching legislation even when FDR refused to support any such national law. She sounded off publicly whenever she heard of New Deal agencies turning a deaf ear to the cries of poor blacks or whites.

Cook looks critically at ER’s failure to speak out about what was happening in Nazi Germany. From as early as 1933, Cook shows, ER had first-hand, reliable information of what Hitler was plotting against German Jews. Yet she said nothing’. (3) In this regard she was all too conventional, mirroring the prejudices of her class. Later, when Jews were trying to flee their homelands and get to safety, ER became an advocate for relaxing immigration statutes, though her efforts by then seemed feeble and late.

While she gained worldwide acclaim as a champion of social justice, first she had to overcome an unhappy childhood, her husband’s infidelity, a domineering mother-in-law, paralyzing depressions, and thunderous public criticism. Her children resented the time and devotion she showered on strangers around the globe instead of on them (did they resent their father’s choices as well?), and all five surviving children led troubled lives.

Nonetheless, ER’s work and pursuits must have given her joys and satisfactions. She had a true partnership with FDR. She had “an extraordinary constellation of female friends” (2) with whom she shared time at Val-Kill Cottage from 1925 until her death. After Franklin died, Val-Kill became her permanent home—and is now the centerpiece of the Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site at Hyde Park.

There was also one special friend, Lorena Hickock, ‘the nation’s first female sportswriter and a star Associated Press reporter, with whom ER exchanged thousands of passionate letters over three decades. To some readers, Cook (herself lesbian) had replaced a bloodless paragon of virtue with a full-bodied portrait of a woman who loved the world in more than the abstract. To others, she had misread the historical evidence in an effort to “out” Mrs. Roosevelt’. (2)

‘Based on Streitmatter’s compilation of the ER letters, more intriguing than the physical aspect of their relationship is the effect Hickock had on Roosevelt’s role as First Lady. Streitmatter argues that Roosevelt—often shy, depressed, and somewhat cynical—did not create the ground-breaking role of a modern First Lady alone.

“When Eleanor wrote Lorena that her life would be ’empty without you,’ the most eminent American woman of the twentieth century was speaking not only of an emotional void but also of a substantive one,” writes Streitmatter. ‘Although Hickock destroyed many letters before her death (in particular, those in which Eleanor had been less “discreet”), the remaining letters paint a romantic love affair—both tender and passionate’. (4)

‘”Hick” had fallen in love with ER in the 1920s. Cook asserts that the language and tone of ER’s letters to Hick prove that they were physical lovers. What else is one to make of “I love you dear one and have wanted you all day”? Cook quotes such letters extensively. But ER, who loved writing long, passionate letters late into the night, expressed similar sentiments to many others, young and old, male and female. She even penned erotic-sounding letters to her mother-in-law, whom she detested’. (3)

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt was deeply feeling, deeply intelligent, compassionate, visionary, accomplished—and enigmatic. Robert Frost’s lines come to mind: “We dance around in a ring and suppose/While the secret sits in the middle and knows.”

November

Katharine Rogers Green

November 14, 1882 – September 2, 1962

Mount Holyoke Class of 1907

An Independent Woman (and Ann Kingman Williams’ great-aunt)

Like many students at Mount Holyoke in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Katharine Rogers Green was called to the mission field in her senior year. At that time, she was older than today’s senior, since she entered Mount Holyoke at the age of 21. She subsequently spent forty years in China, returning every ten years for a year of Home Leave. Never married, her life revolved around the mission, the children she taught, and her extended family when she was home on leave. She was my mother’s aunt, my great-aunt, and her name is carried by one of our daughters and one of my sister’s daughters. She was, indeed, a woman of formidable abilities and strengths.

Katharine was the seventh of eight children, and the only daughter, of Garret E. Green and Caroline Voorhis Green. Born in Nyack, New York, and brought up in the Dutch Reformed Church (Reformed Church of America), she was kept under the watchful eyes of not only her parents, but all of her brothers. One can only imagine her frustration at not being allowed the privileges and freedom of her brothers, as she was a strong and forceful character. When Katharine was fourteen, the family moved to Brooklyn, New York, where she attended public school and then Packer Institute, a school for girls in Brooklyn, before going to Mount Holyoke in 1903.

While at Mount Holyoke, she majored in English Literature. Her growing interest in becoming a missionary probably stemmed from the religious enthusiasms of the times and in her delight in independence from her family. As to my sources, there are many family stories, histories of the Amoy Mission of the Reformed Church of America, and of other schools and missions to which she was posted and also include records from the Mount Holyoke archives.

In 1907, the year of Katharine’s graduation, China was still in turmoil following the Boxer Rebellion (1900) and continued unrest at the turn of the century. Nonetheless, she shipped out to Amoy (now Xiamen), where she took a position at The Bridgman School and studied the Chinese language for a year. This school was one of many in the 19th C. which had an affiliation with Mount Holyoke, either having been founded by or engaging teachers from Mount Holyoke College. From there, she went on to become superintendent of the Fukien Girls School, also in Amoy. She taught English, and often trekked into the countryside on evangelistic trips. In an effort to encourage self-sufficiency as well as fresh food, she developed vegetable gardens at the school, where the girls were taught to tend the crops. This was met with distrust. Indeed, it took years to be accepted, as agricultural labor was viewed to be a step backward in the education of the girls, most of whom, if not all!, had come to escape from rural life. But Katharine persevered, and her Industrial Arts program flourished.

In 1928, Katharine started to divide her year between her work in Amoy and the Christian Literature Society in Shanghai. She spent June 1 to November 1 of each year in Shanghai because of life-threatening allergies in the low-lying river environment of Amoy. While at the Christian Literature Society, she published many books and articles. Most of these are short biographies of famous people or religious study guides, but she also wrote several volumes of Shakespeare’s plays in ‘simple English’. A number were translated into Chinese, including a biography of Mary Lyon.

It was customary for missionaries to return on Home Leave periodically. When she was on leave, Katharine lived with family members and lectured on various topics having to do with China. She shared her extensive knowledge of Chinese folk-lore and symbolism with clubs and study groups. Any proceeds from these lectures were sent back to China for emergency and relief work. Years later, I (Ann) remember poring over Chinese wood carvings with her, looking for the ancestral clouds on which the ancestors were placed, the lotus trees and other symbols. We are fortunate to own and enjoy many of the objects that she brought home with her.

In August 1937, Katharine’s work in Amoy was interrupted by Sino-Japanese hostilities. She returned to America after having been under house arrest and then interned in a prison camp in Shanghai. She ultimately returned to China, but was again forced to leave because of the advance of Chinese Communists in 1947-1949.

After her return to the U.S., she worked as a translator for the Voice of America, taught English as a Foreign Language to both Hungarians and Argentines (knowing neither Hungarian nor Spanish), and volunteered extensively in church work, hospitals and for the Red Cross. Her life was one of service to others.

In 1960, the Mount Holyoke College Alumnae Association sent out a questionnaire, which she dutifully answered. The primary questions were about marriage, husband, husband’s schooling and career, and family. Aunt Katharine’s answers were pointedly sharp and brief. When asked if she had undertaken any advanced study, and if so, at which institutions, she snapped “yes, the Chinese languages for 40 years.” Another time, when answering a similar questionnaire, on volunteer work, asking for names, dates, and positions in societies and on boards, this was her response: “In missionary work it is impossible to separate volunteer work from regular; and it is all social, educational, philanthropic and religious.”

Is it any wonder that Katharine Rogers Green left such an indelible impression on her great-nieces?

November (2)

Shirley Chisholm

named to the Purington Chair at Mount Holyoke in 1983

(born November 30, 1924, Brooklyn, NY; died January 1, 2005, Ormond, FL)

“My greatest political asset, which professional politicians fear, is my mouth, out of which come all kinds of things one shouldn’t always discuss for reasons of political expediency,” she once said. Shirley Chisholm was unafraid of controversy. Her unpredictability and brashness often left her at odds with her colleagues, black and white. But that did not stop her from using her incisive speech to excoriate Congress when she felt it was being unresponsive or from lambasting members of the Congressional Black Caucus, of which she was a founding member in 1969.

She was born Shirley Anita St. Hill in Brooklyn. She was the oldest of four daughters of a Guyanese father who was a voracious reader and student of political activist Marcus Garvey and a Barbadian mother who groomed her girls to use their poise and education to take their rightful place in the world.

From age three to eleven, she (and two younger sisters) lived in Barbados with her maternal grandmother. She attended the rigorous, British-style schools, where she learned to speak and write easily, she said. In Barbados, she also gained the clipped Caribbean accent evident in her speech.

In 1934, she moved back to Brooklyn and later graduated cum laude from Brooklyn College. She made the decision there to become a teacher, believing that she could improve society by helping children. Her first job was at a child-care center in Harlem, where she worked for seven years. She attended night school at Columbia University and received a master’s degree in early childhood education in 1952.

She became director of a day-care center and then served as an educational consultant with the Division of Day Care in New York from 1959 to 1964. Her nascent interest in politics, which began at Brooklyn College, bloomed in the 1960s when she became engaged in local Democratic politics. In 1964, she was elected to the New York State Assembly, where her independent style took shape.

After four years in the Assembly, she ran against James Farmer, the former national chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality, to win the newly created 12th District of New York (Bedford-Stuyvesant). She built a grass-roots campaign to counter Farmer’s well-financed operation and used the slogan, “Fighting Shirley Chisholm: Unbought and Unbossed,” which came to characterize much of her political career.

As a ‘freshman’, Chisholm was assigned to the House Forestry Committee. Given her district, she felt the placement was a waste of time and shocked many by demanding reassignment. She was placed on the Veterans’ Affairs Committee. Soon after, she voted for Hale Boggs as Majority Leader over John Conyers, even though Boggs was white. As a reward for her support, Boggs assigned her to the much-prized Education and Labor Committee.

In 1972 she made a bid for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination, received 152 delegate votes, but ultimately lost to Senator George McGovern. She said she ran for the office “in spite of hopeless odds,” “to demonstrate sheer will and a refusal to accept the status quo.” Mrs. Chisholm’s candidacy signaled significant change on the American political landscape as a new generation of blacks and women made its way into mainstream politics.

To the surprise and displeasure of many, she visited presidential candidate George C. Wallace, once a strident segregationist, after he was shot in 1972. And she endorsed Republican Nelson A. Rockefeller as Vice President from the floor of the House in 1974.

In a 1982 interview with a Washington Post reporter on the eve of her retirement from Congress, she responded to criticism about her support of Rockefeller’s nomination and her hospital visit to Wallace. “I don’t take one incident of a person’s total life and hang the person with it forever,” she said, adding that Rockefeller’s support when she was in the state legislature outweighed her own reservations about him.

“Just like George Wallace standing in the door of the University of Alabama preventing black young people from attending…. I went to the hospital when he was shot…. and later he was the man who helped get the votes on minimum wages for black women…. I believe there is good in everybody, maybe that’s a weakness I have.”